Carotid body Tumor

Paraganglioma, also known as Extra-adrenal pheochromocytoma, glomus tumor, or chemodectoma, is a rare tumor of the head and neck, which is derived from the neural crest.

They can occur throughout the body in association with the sympathetic and/or parasympathetic ganglion. The most common locations affected by paragangliomas are the carotid body, jugular vein (‘glomus jugulare’), vagal body (‘glomus vagale’), and middle ear (‘glomus tympanicum’).

Multiple tumors are present in 5% of cases. There is a female predominance in all locations except the carotid body; the average age of affected patients is 50-60 years (in general, pheochromocytomas are associated with patients in their 20s and 30s and show no preference between genders).

Paragangliomas are associated with both von Hippel Lindau disease and multiple endocrine neoplasia II (MEN II).

In addition, a person’s risk reportedly increases ten-fold with chronic exposure to high altitudes, suggesting a possible correlation with decreased oxygen tension.

Carotid body tumor is the most common type of paraganglioma .

The carotid body was first described by von Haller in 1743 and is a round, reddish-brown to tan structure found in the adventitia of the common carotid artery. It is locate on the posteromedial wall of the vessel at its bifurcation and is attached by "Mayer's ligament" through which the feeding vessels run ( primarily from the ascending pharyngeal and lingual branches of the external carotid ). The function of the carotid body is related to its role in the autonomic control of the respiratory and cardiovascular systems.

Histologically, carotid body paraganglioma resemble the normal architecture of the carotid body. The tumors are highly vascular, and between the many capillaries are clusters of cells called Zellballen.

Presentation and diagnosis :

The vast majority of carotid body paragangliomas present as slowly enlarging(~5mm per year), non-tender neck masses located just anterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle at the level of the hyoid. The classic finding is a mass in this location that is mobile in the lateral plane but limited in the cephalocaudal direction. Occasionally the mass may transmit the carotid pulse or demonstrate a bruit or thrill. They tend to splay the carotid bifurcation as they enlarge and can extend along the internal carotid to skull base. As these tumors enlarge, progressive symptoms of dysphagia, odynophagia, hoarseness and other cranial nerve(IX-XII) deficits appear.

Imaging :

I. USG

On ultrasonography (US), the demonstration of a solid, well-defined, weakly echogenic mass located within the carotid bifurcation safely differentiates and excludes purely cystic masses. on color Doppler imaging, hypervascularity with a low-resistance flow pattern is seen.

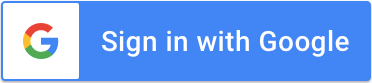

II. CT

Demonstrates a solid mass that shows homogenous enhancement on intravenous contrast administration. The presence of uniform contrast enhancement and large feeding vessels into the tumor is not seen in lymph node masses and schwannomas. The incorporation of large feeding vessels is typical of carotid body paragangliomas whereas schwannomas tend to displace the adjacent vessels. The medical displacement of the internal carotid artery is considered to be specific for tumors of vagal origin whether they are schwannomas or paragangliomas.

Demonstrates a solid mass that shows homogenous enhancement on intravenous contrast administration. The presence of uniform contrast enhancement and large feeding vessels into the tumor is not seen in lymph node masses and schwannomas. The incorporation of large feeding vessels is typical of carotid body paragangliomas whereas schwannomas tend to displace the adjacent vessels. The medical displacement of the internal carotid artery is considered to be specific for tumors of vagal origin whether they are schwannomas or paragangliomas.

III. On MR

non-contrast T1W images demonstrate a heterogeneous mass with isointense signal intensity at the carotid artery bifurcation with multiple serpentine areas of low signal intensity representing flow voids throughout the mass. On T2W images the tumor shows hyperintense signal intensity. On intravenous gadolinium DTPA contrast administration, the tumor enhances intensely. MR characteristics include a "salt and pepper" appearance due to multiple serpiginous vascular channels that produce the dark 'pepper' and small hemorrhages that produce focal hyperintensities on T1, the 'salt' appearance.

non-contrast T1W images demonstrate a heterogeneous mass with isointense signal intensity at the carotid artery bifurcation with multiple serpentine areas of low signal intensity representing flow voids throughout the mass. On T2W images the tumor shows hyperintense signal intensity. On intravenous gadolinium DTPA contrast administration, the tumor enhances intensely. MR characteristics include a "salt and pepper" appearance due to multiple serpiginous vascular channels that produce the dark 'pepper' and small hemorrhages that produce focal hyperintensities on T1, the 'salt' appearance.

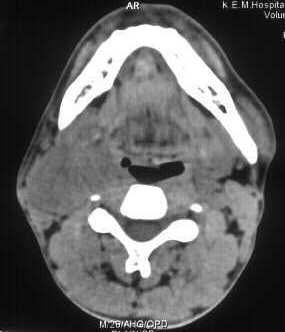

IV. Carotid Angiography:

Although it is an invasive test, carotid angiography is by far the most useful diagnostic test for paragangliomas. This modality can establish the diagnosis, demonstrate multiple lesions, determine the size and vascularity, and evaluate the tumor blood supply. Additionally, it can be modified to include selective, controlled balloon occlusion of the internal carotid artery to evaluate the cerebral cross-flow.

The classic, pathognomonic finding on arteriogram is widening of the carotid bifurcation by a well-defined tumor blush ("lyre sign"). It should be emphasized that angiography of both carotid systems is required to rule out bilateral tumors. MRI with gadolinium (tumors as small as 5 mm) and contrast CT are also effective imaging modalities and are non- invasive

Treatment:

For small tumors (<3 cm) in good surgical candidates, surgical resection is the treatment of choice.

Treatment:

For small tumors (<3 cm) in good surgical candidates, surgical resection is the treatment of choice.

For larger tumors in patients who are not surgical candidates, radiation—with or without embolization—is the treatment of choice.

Most patients are surgical candidates, and for those with large tumors, preoperative embolization has increasingly become the standard of care to aid in safer resection. No complication is anticipated in ligation of the external carotid artery and larger tumors render themselves easier to excision. The internal carotid artery must be saved under all circumstances. Cranial nerves also should be saved even if the nerve has to be shaved away from the tumor.8 If the resection is not complete, radiotherapy should be used.

Shamblin introduced a classification system based on tumors size.

Group I included small tumors that could be easily dissected away from the vessels.

Group II included paragangliomas of medium size that were intimately associated and compressed carotid vessels, but could be separated with careful subadventitial dissection.

Group III consisted of tumors that were large and typically encased the carotid artery requiring partial or complete vessel resection and replacement.

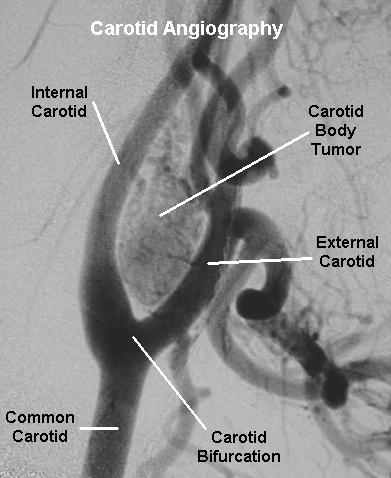

Embolisation

The primary benefit of preoperative embolization of a carotid body tumor is to reduce intraoperative blood loss and facilitate operative tumor resection.

The goal of embolization is to selectively obliterate the abnormal vascular structure while maintaining normal blood flow through the carotid artery arcade.

Deployment of microcoils is one method of embolizing carotid body tumors. Helical platinum nonferromagnetic microcoils placed as deeply as possible in the artery avoids risk of inadvertent embolization to the brain.

To enhance the effect of occlusion by microcoils, particle (PVA, gelfoam) embolization can be added to the procedure.

Several other techniques of carotid body tumor embolization have been reported.

Tripp et al described preoperative vascular exclusion for carotid body tumors. Multiple feeding arteries to the tumor were excluded by percutaneous placement of two covered stents in the external carotid artery.

Horowitz et al reported the use of ethanol injection with simultaneous balloon occlusion. With nondetachable balloons placed in the proximal internal and external carotid arteries, a microcathether was placed into the feeding vessel, and ethanol was infused over 15 minutes. The follow-up arteriogram demonstrated complete tumor devascularization with continued normal carotid artery branches.

Embolization has also been applied by a direct percutaneous approach after failure of endovascular particle embolization. Using duplex ultrasound guidance, N-butyl cyanoacrylate was directly injected into the tumor. Simultaneous catheter access assisted in imaging and demonstrated complete embolization.

The tumors have a 10% recurrence rate after resection. Carotid body tumors uncommonly (5%) undergo malignant transformation, with metastases.